Tony Boycott (aka AB(Dr) in Upper Canada Cave, Mendip. Background photo by Linda Wilson.

There's been caving at home and abroad, and our occasional correspondent, the Reluctant Caver, demonstrates one of the many things that can be done with a geography degree!

Your overworked editors are looking forward to news of all the things members will be getting up to over the summer break, so take lots of photos wherever you're going and have a great time!

You can find all the back issues of the monthly newsletter online. So if you're relaxing in the sun somewhere, take a look at what the club has been up in past months and years.

Linda and Alex

Area left by 2009 dig. Note burnt layer under the boulder. Photo by Linda Wilson.

A recent archaeological excavation by a small team from Bristol University Archaeology department assisted by UBSS members and led by Dr Kostas Trimmis, is seeking to further investigate human activity at Read’s Cavern in the Mendips as Charlotte Harman explains ...

A section was cut in the area of previous UBSS excavations within the cave which contained a large charcoal deposit left by fires. These had been partially unearthed during a previous excavation at the site in 2009 and chosen for further investigation since burnt assemblages offer an avenue through which we can explore previous anthropogenic activities.

Charlotte wielding the archaeological pickaxe. Not a camel hair brush in sight. Photo by Linda Wilson.

Once the feature had been cleaned back to expose the stratigraphic layers, it was clear that not only did the charcoal layer extend below a fallen boulder around which sediment had built up, but that there were three separate layers of charcoal with deposits of natural sediment in between. This would suggest that there are at least three different incidents of fires in this part of the cave. A small animal rib bone was discovered in one of these layers as well as possible fragments of crushed bone which were collected for further analysis.

The plot thickens ... or rather the trench deepens. Photo by Kostas Trimmis.

Samples of charcoal were taken for C14 dating at the Bristol Radiocarbon Accelerator Mass Spectometry (BRAMS) facility to help construct a chronological sequence for this feature.

Further samples of the clay sediment were collected from the trench for environmental processing and further archaeobotanical study, with the aim of examining potential plant assemblages found in archaeological contexts. We intend to use flotation methodology, so any charred botanical remains will be extracted from the samples for analysis under a microscope. Although plants, as biological organisms will usually decay with time, under certain conditions they can be preserved in the archaeological record. Carbonised botanical remains are those generally found on UK sites due to the climate here (Vareilles et al., 2021; Veen, Hill, and Livarda, 2013). Through comparison of external morphological features of a carbonised plant part, such as a seed, with their modern equivalent, we can identify botanical species (Renfrew 1973: 5). The purpose of this is to provide a more holistic understanding of the relationship between people, plants and the environment they cohabit in and how this has changed throughout pre-history and history.

Recording. Kostas Trimmis (left) and Joel Sullivan (right). Photo by Charlotte Harman.

The final task undertaken in the cave was to fully record the section and the trench by itself and within the surrounding area of the cave, through 3D Lidar based photogrammetry imaging and archaeological illustration. The reason for implementing both forms of recording is because each highlights slightly different aspects of an excavation. A photo is able to convey what the trench section or artefact looks like at that moment, however a technical drawing can provide a more interpretative account of what has been discovered.

Keep an eye out for future updates on whether these samples can reveal anything new about Read's Cavern. Thanks to Linda Wilson, Jan Walker and Felix Arnautovic for their help underground.

References

Vareilles, A. de et al. (2021) ‘Archaeology and agriculture: plants, people, and past land-use’, Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 36(10), pp. 943–954. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2021.06.003. (Accessed 1 October 2022)

Veen, M. van der, Hill, A. and Livarda, A. (2013) ‘The Archaeobotany of Medieval Britain (c ad 450–1500): Identifying Research Priorities for the 21st Century’, Medieval Archaeology, 57(1), pp. 151–182. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1179/0076609713Z.00000000018n/a. (Accessed 1 October 2022)

AB(Dr) navigating his favourite scaffolding.

Arm-swinging passage, he said. You'll enjoy it, he said. There's a streamway, he said. Well, the moral of this story is always double check information provided by AB(Dr) (aka Tony Boycott) against a reliable source. The problem arises when the cave concerned is one of Mendip's lesser known sites, so reliable sources are few and far between, and mostly consist of those hardy - and frequently deluded - souls who opened up the cave in the first place, so their recollections are seen through the prism of rose (and by rose I really mean red ochre) tinted glasses.

AB(Dr) in one of the gravelly grovels.

To be fair (which I'm usually not where Tony is concerned), I did enjoy the trip, but there weren't many opportunities for swinging my arms as I strode down the main passage, although I did rotate them a few times whilst negotiating the tight bit, with the yells of "It's not a squeeze!" reverberating from Tony (behind me), every time Alan Grey (ahead of me) referred to it as a squeeze. With the benefit of hindsight, I agree with Alan on that subject. There was enough thrutching involved for it to count as a squeeze.

AB(Dr) exiting the not-a-squeeze. His arms might be swinging a bit here.

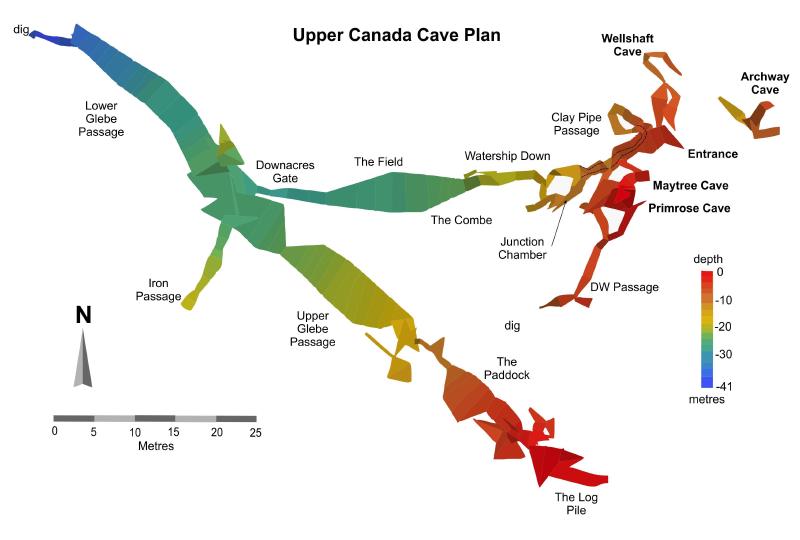

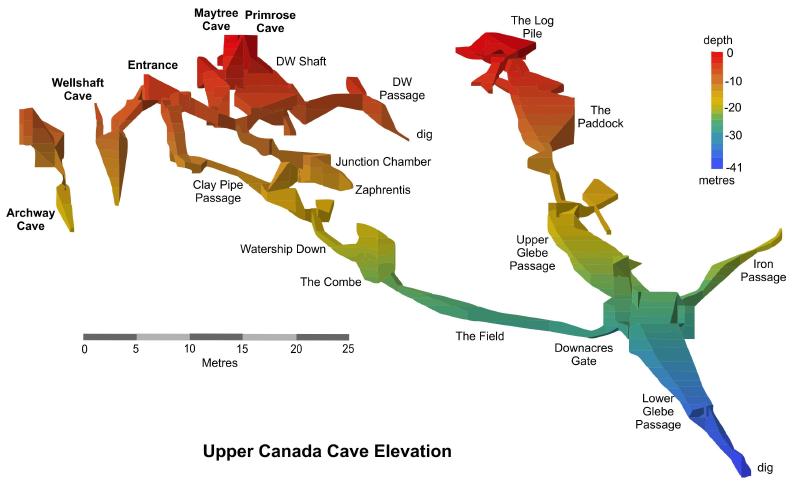

For those who might even be tempted by a visit, Upper Canada Cave, 346 m long and with a vertical range of 35m, can be found in woodland at Canada Combe, Hutton. NGR - ST 36027 58164. It was first opened by ochre miners in the 1750s and was subsequently refound in 1828. This site and the nearby Bleadon Cavern yielded a large number of animal bones that can now be found in The Quaternary Mammal Collections at the Somerset County Museum, Taunton. These range in size from dwarf hamsters and mountain hares to straight-tusked elephants and mammoths, with predators such as red fox, wolf, spotted hyaena and lions.

Survey, copyright Axbridge Caving Group 2016. Used with their kind permission.

The cave was once again lost but in 2007 Upper Canada Cave was re-discovered and in 2012 a digger was used to open up the cave and the surrounding area. Numerous shafts have been re-opened in the woodland, many very close together, forming pit traps for the unwary as I followed in Alan Grey's footsteps, with him saying things like: "Don't go down that one, it's full of unstable boulders."

Survey, copyright Axbridge Caving Group 2016. Used with their kind permission.

A large, overgrown hollow has a bed of stromatolites at its northern end, 4m high and 3m wide, formed in Black Rock Limestone.

A short fixed ladder leads down into the cave and I was quickly ordered to admire Tony's favourite scaffolding, an engineering feat he was inordinately (and quite reasonably) proud of. After this, a series of gravelly slithers leads down to the 'not-a-squeeze' and thence to the 'almost-but-not-quite-arm-swinging passage'.

Big lumps of rock with a very high lead content.

The cave is very ochreous and contains some very impressive chunks of lead ore. But for the record, there's no streamway, unless you count the one that formed the passage in the first place, there are very few arm-swinging opportunities and it's not in Canada. But I did enjoy it, despite coming out absolutely covered in red ochreous mud. To my amazement, Tony agreed to put my caving kit through his washing machine, thus ensuring that I won't hear a word against him!

If anyone would like to visit the cave, let me know and I can arrange a trip as the diggers have an arrangement with Avon Wildlife Trust who own the woodland.

ADVANCED BONDAGE TRAINING Zac Woodford wishes it to be known that he wasn't skiving off the recent working weekend at the hut, he was actually at an expedition training day over in the Forest of Dean.

Zac Woodford wishes it to be known that he wasn't skiving off the recent working weekend at the hut, he was actually at an expedition training day over in the Forest of Dean.

Having missed the Cambridge expo training due to dissertation wonkery I signed on to the Dachstein expedition training weekend instead. Getting there was entertaining as I had to go via Bristol Airport to pick someone else up. However, that was the day the South West decided to turn itself into a car park meaning the quickest way to the old Severn bridge was via Avonmouth.

Having finally reached the Gloucester Cave Rescue depot, our excellent hosts for the weekend, we had a look around. The garage was strung up with several miles of rope on every SRT configuration you can think of, flying traverses to Tyrolenes. Limited organisation was carried out that night with our prevailing attitude being, we'll sort it tomorrow morning.

When tomorrow morning came we split into several groups to focus on different aspects of expeditions, simple SRT, advanced SRT, bolting and emergencies. I prioritised simple SRT as a refresher but soon found I exceeded that and so moved on to more advanced stuff. In the afternoon I learnt how to use the Cave Link and then went through the kinds of emergency equipment we might need.

Advanced bondage techniques and and explanation of what to do if you meet a yeti.

That evening Joel Corrigan gave a talk about the Dachstein while we all enjoyed fish and chips courtesy of the local chippie. Thomas Matthalm then gave a talk about the longest cave rescue in Europe back in 2014 which he was at the heart off. I won't repeat it here as it's best experienced in person.

The next day I pursued Tony Seddon in search of a new oversuit. I also trialed a new chest harness during the day's SRT practice. By the end of the day I had a new oversuit, chest harness and gear loop.

Driving back, the South West was once again a car park. But I got to the airport with plenty of time to spare before heading back to Bristol.

Zac Woodford

Pluto's Bath, OFD 1. Photo by Linda Wilson.

Zac isn't the only one who's made their way over the bridge recently. Linda Wilson decided to try out her dicky ticker in OFD on the late May bank holiday weekend and survived the experience, although she's not she this was quite what the consultant meant be resuming her 'normal activities'.

The bank holiday weekend dawned surpisingly fair; hot but with enough of a breeze to keep you cool on the walks to and from the Wealdon Cave and Mine Society hut colloquially known as The Stump. We'd taken the campervan over and installed ourselves outside the tool store, where we could hook up to the electricity. We used the van to sleep in with the dogs, and spent the evenings in the hut, with our friends Peter and Beni Burgess. As Peter had made the hut booking, the dogs were allowed in the cottage, so it was idea for us (and them). To our suprise, even though it was a long weekend, we were the only people staying there.

Beni Burgess crossing one of the deep pools in the streamway.

On Saturday, Peter, Beni and I walked down to OFD 1 and wombled up the streamway to the boulder choke and back, with me taking some photos en route. The water was very low. The only party we saw underground was a small group from Cardiff uni. The walk up hill back to the cottage was more strenuous than the caving trip, and reminded me why I always liked One to Cwm Dwr or One to Top as a trip as that allows the up hill bits to be done underground where you can't get bitten by mozzies. When I was able to check the info from my Fitbit, I was pleased to learn that my heart beat hadn't gone over 120 beats per minute, as I'd been advised not to exercise for long periods at over 130 bpm. To be honest, I didn't have a clue what caving would do to it, but as I felt fine, that was all to the good.

Graham with Gwen (left) and Trigger (right) at Top Entrance.

We took a day off on Sunday and walked the dogs in the sunshine, including taking them up to Top entrance. A fair amount of time was spent lounging around at the South Wales Caving Club (SWCC) Hut on the opposite side of the valley to the Stump. It was a working week for SWCC, which meant I got to see a few people I've not seen for absolutely ages, including Bob Peat who I probably last saw about 30 years ago.

The Mini-Columns, OFD Top.

Monday was equally pleasant. Peter and I decided to go for a womble in Top to the Bedding Chambers, a part of the cave I've not visited for ages. Naturally, I got distracted on the way and sidetracked us into a visit to the Mini Columns, where I last went with Carol Walford and Bob Mehew. I remembered a rather awkward climb up from a short section of passage on the right, not far from the entrance. Fortunately, Peter knew an alternative route and we very quickly admiring our newly-added objective. From there we backtracked slightly to the route to the Bedding Chambers and made our way onto the Bedding Chambers. This is an area of the cave that doesn't get many visitors, but it's very well worth a detour. There's an undistrubed air about the whole area, with some fantastic rock shapes and lovely formations.

Rock shapes in the Bedding Chambers, OFD Top.

Rock shapes in the Bedding Chambers, OFD Top. The trips were a great combination of walking, clambering, squeezing and thrutching. In a couple of places, I found my oversuit sticking itself like glue to the mud of a squeeze while I tried to move forward! I ended up laughig so hard trying to get into the section of not-very-tight-at-all. Once again, my heart rate didn't rise to unacceptable levels, despite my collapse into helpless laughter trying to unglue myself from the cave, although I could pretty much track my progress through the cave on the Fitbit read out.

This time, the walk was downhill, and much more pleasant and I relaxed in a very fine shower before another stroll over to SWCC and more nattering. I can thoroughly recommend that seldom visited area of OFD for anyone who wants a chnage from the usual trade routes. Many thanks to Peter for his hospitality.

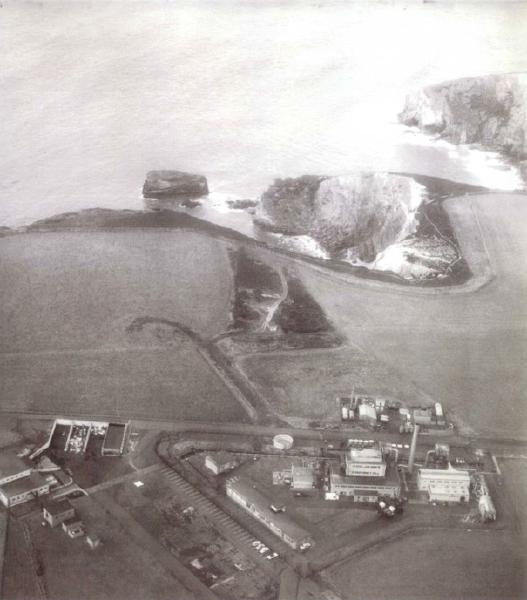

CDE Nancekuke in the early 1950s.

For those cavers graduating this summer and vaguely wondering where their career paths might lead, our occasional correspondent, the Reluctant Caver, tells the (true) story of some of their Adventures with a Geography Degree. (The eagle-eyed amongst the readership might even be able to hazard a guess at their identity.)

After six years at Bristol doing a geography degree and a PhD in karst hydrogeology during which I had a love-hate relationship with Mangle Hole (if you’ve not been there, it really isn’t worth the effort), I was encouraged to stop being a free-loader and earn some money. I therefore entered the world of the environmental consultant with one of my first jobs in the early 90s being on a piece of wasteland in Avonmouth with surprisingly little vegetation – I soon learnt why! Over the years, other than working on the occasional limestone quarry I did little by way of working on any holes in the ground, until I was sent to a WWII airfield, RAF Portreath, on the north coast of Cornwall. Happy days, I thought, sun, sea and pasties. I was in for a rude awakening.

Such an inviting place for a holiday! CDE Nancekuke in the early 1950s.

As well as RAF Portreath, the site was known as Chemical Defence Establishment Nancekuke, or the place where the MOD manufactured Sarin nerve agent during the Cold War. When the site closed the Sarin was destroyed and all of the old buildings and plant were decontaminated, dismantled and the remains placed in a series of dumps along with decontaminated vessels used to manufacture mustard agent in WWII. My job was to assess if any chemical agent residues remained in the ground or groundwater given that records were incomplete and the decontamination was not done to modern standards.

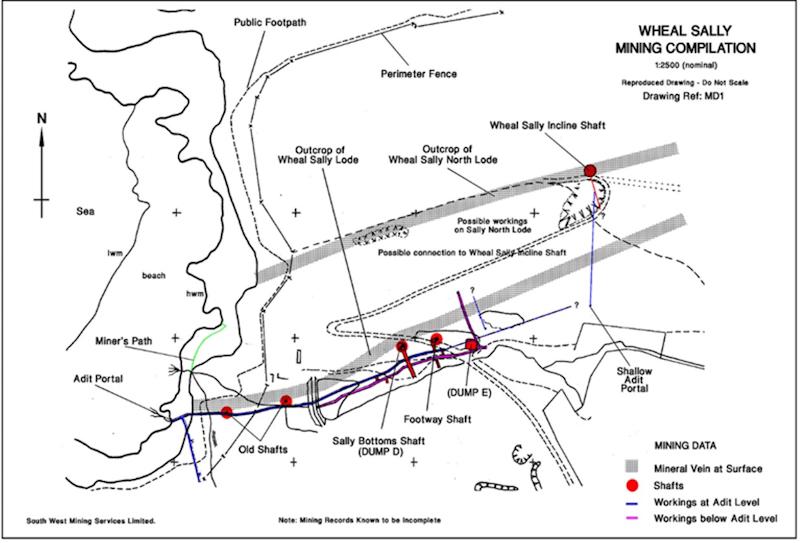

All very interesting, but I can hear you keen youngsters screaming what has this got to do with caving? Well, two of the dumps were former mine shafts associated with the Wheal Sally lead and zinc mine which was closed in the early 1900s, the condition of which could best be described as poor and realistically as a fucking nightmare waiting to either fall on you or drown you [also my scepticism that the name “Sally” (i.e. a bright and cheery lass) for a mine would be completely misleading, as any of you who have been down Singing River Mine will attest (i.e. it does not contain a singing river)].

The only access to the mine was via an adit entrance at the bottom of a 60’ cliff via the old miners' “path” (read sub-vertical becoming vertical exposed and slippery climb) with the adit only accessible at low tide. The adit, which had a small stream flowing out of it, was open and led to two passages, the one to the right was quickly explored and only 100m long with no workings. It did however contain a corroded and seaweed encrusted conical device which resulted in a bomb squad call out but just turned out to be an old fire extinguisher. The left passage was more interesting leading to the main workings, although there was a collapse only 20m in completely blocking the way on. The collapse was beneath a shaft, the only one into the mine that had been adequately capped as it was adjacent to the South West Coast Path.

Mine plan showing shaft locations.

As this was proper grown up work we needed a comprehensive health and safety plan covering off climbing, mining, ground gas, working near water and of course chemical warfare agents along with asbestos (that well-loved material for lagging pipes in the 1950s). We needed a mine manager and mine engineer in order to “re-open” the mine to allow the inspection to be completed and we needed someone to manage the whole thing and who understood more than a little about environmental legislation and groundwater movement. I also had to learn a whole new vocabulary, that of an 18th century Cornish miner. We even ran emergency simulations with the local emergency services just in case it all got a bit exciting. To add to the complexity the area was a Site of Special Scientific Interest and so we needed consent from English Nature (Natural England, as they're now called) to work in the area.

Adit entrance at beach level (left)and collapse beneath first shaft (right).

Adit entrance at beach level (left)and collapse beneath first shaft (right).Following a lot of research we pieced together the history of the site and mine layout and got our engineering team to start gaining access by installing a ropeway and ladders down the cliff to allow safe access. We then completed bat surveys prior to works which demonstrated that the site was not used as a roost. We moved the first mound of collapse material and installed a lot of props beneath hanging death and planks over submerged shafts, in addition to fitting a robust gate (for obvious reasons). We found further chokes, some of which were holding back large volumes of water so quite a bit of pre-pumping was required to gain access before rock was removed. We also temporarily diverted a stream at the surface as this was partially sinking through the ground and into a former shaft making things a little unstable in the mine below. Power was provided by a substantial compressor parked on the cliff tops with air lines running down to the adit.

Stabilisation works to allow safe access.

As digs go it involved some major engineering works and a lot of local knowledge regarding Cornish mining practices and how the old boys would have worked the mineral veins and stacked the waste rock.

More stabilisation work.

With tides limiting our working periods and winter storms stopping work completely it took a couple of years to get the mine open safe to access as far as the two dump areas. These were duly assessed and samples collected for lab analysis. The further reaches of the mine were very unstable and as they had not been used for disposal were not accessed. Although some of the stabilisation works look robust they were all temporary, solely to facilitate the inspection and future access to the mine (which would require a thermic lance to get through the gate) is definitely not recommended.

The end of the rainbow!

In addition to entering the mine from the adit, we drilled an angled borehole above ground into one of the shafts and excavated the “ladderway shaft” at the surface. Initial assessment of one of the areas denoted by the obligatory warning sign as dangerous and not to be entered (the gorse being more of a deterrent than the 5’ high plastic fence) turned out to be nothing more than a degraded concrete pad for a water pump. Our mine manager got the old mine survey out along with his tape measure and identified where the shaft really was – the old surveys turned out to be surprisingly accurate. A little digging revealed a number of old mustard cooking pots. In full NBC gear I got up close and friendly with a few of these to take some samples for more lab analysis and was then subject to precautionary decontamination procedure.

Once the inspection was finished, we installed a borehole from ground surface into the adit to allow water sampling without having to descend the cliff. Sampling continued for ten years after completion of the inspection. Remediation works were completed to securely cap the former shafts at the surface and a mine abandonment plan was filed with the Mines Inspectorate. No chemical warfare agents were found in any soil or water samples, which was great news.

So, for any of you out there doing a geography degree, just beware, you may learn far more than you ever wanted to know about Cornish mine terminology and chemical warfare agents, and possibly being interviewed for the local news.

For those wanting more information (the most fun documents are from the conspiracy theorists) there are plenty of articles online and a few videos from a well-known internet site that also shows you how to remove a Ford Escort gearbox should you ever need to do so.

There are also a few scholarly articles out there if you have severe sleeping problems (e.g. Hobbs SL, 2013, Assessing and managing the long term risks and liabilities at a closed Cornish mine used for waste disposal, Mine Closure 2013 — M. Tibbett, A.B. Fourie and C. Digby (eds), pp.509-522). In addition, Cornwall Council hold copies of the mass of reports that we filed following the inspection of former CDE Nancekuke.

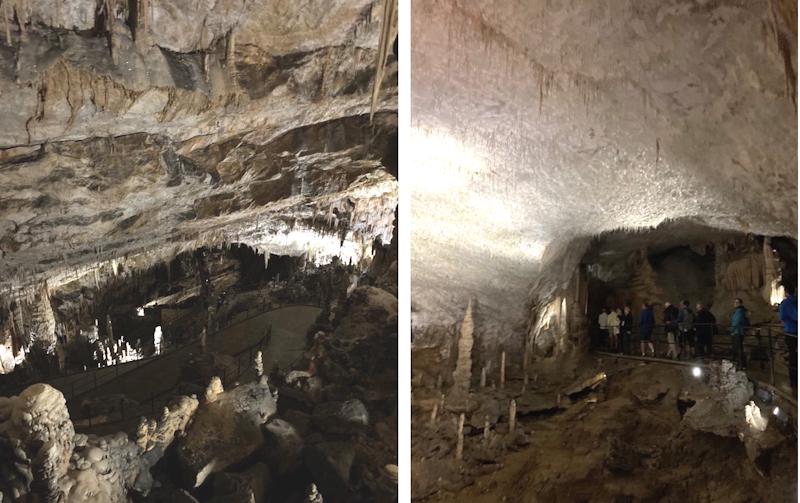

The start of the main showcave tour in Postoynska jama.

Sick of slogging ariound Goatchurch? Bored with endless boulders in the entrance to Draenen? Yes, what most caves need is a train. Yes, you heard that correctly, a train. So settle in for the ride, as Alex Little did with friends Ewan, Martin, Tom, Bryan, Ben, Luis, and Harrison during a trip in Slovenia.

A short trip from the Slovenian capital of Ljubljana, Postojnska Jama (Postojna Cave) is the largest in Europe (it’s probably not, and will depend greatly on your definition of ‘large’...) The approach involves mighty difficult terrain, including pavements and zebra crossings. Novice and experienced cavers alike should be warned of the most perilous obstacle: a ticket office.

Anyway, what welcomes visitors to the site is an array of catering facilities and tat shops. Entrance to the cave is only by hourly tour, so in the wait we visited the vivarium: a small museum-zoo hybrid, in a cave, dedicated to teaching about life in caves, with tanks showing the troglodytes of the area, from critters like shrimp and woodlice, to the mighty olm.

An olm (Proteus anguinus), an aquatic cave-dwelling salamander, in the vivarium.

An olm (Proteus anguinus), an aquatic cave-dwelling salamander, in the vivarium.Spare half-hour spent, we stepped blinking into the blazing Mediterranean sun and queued for the tour. A short while later, we entered the cave. And boarded a train.

(Left) Train. Note there’s enough space that they fit a second track. (Right) In the 'station'.

Not what one usually expects on a caving jolly, but great fun. The ride is a good 10 -15 minutes long, the first exhibition of the immensity of the cave. Eventually, we arrived at the station (yes), and began the tour proper with a challenging ascent up a convenient concrete path (which is ever-present from now on), to the highest point of the cave. From here, the ceiling is still tens of meters above, and looking back reveals an endless field of ‘mites and ‘tites.

The descent (left). Roof spaghetti (right)

Next, we walk back down a few tens of meters, cross a bridge, and enter the three ‘beautiful caves’, including the Spaghetti Cave, with a dense roof of very thin stalactites.

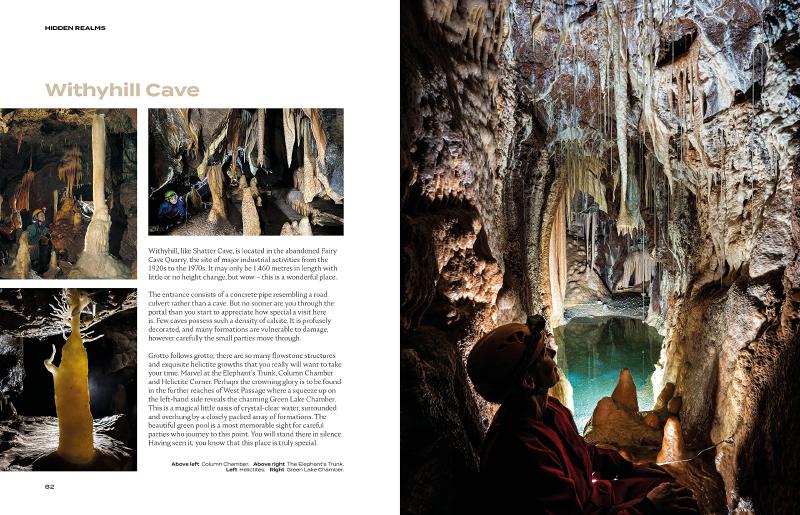

The tour passes through several other interesting, attractive, and vast chambers and features, over about an hour. Towards the end is a massive reddish column next to a comparably grand bright white stalagmite. The tour concludes with passing a tank of a few olms, a in-cave gift-shop/post-office combo, and the Concert Hall.

Large chambers and interesting formations.

Large chambers and interesting formations.

The column and stalactite (left) and the Concert Hall (right).

The return train journey ends with a view of a river from high above (presumably the river that carved the cave), complete with a confused-looking wild bat. Finally, before returning to the surface, visitors are presented with the opportunity to purchase a photograph of themselves taken during the trip, much like at a rollercoaster! The only downside is that it was taken immediately after passing the ticket machines with no warning, so the image is invariably unflattering and not at all cave related.

River (left) and vivarium chamber (right)

Fish in vivarium.

Closing thought: not enough squeezes. (But there was a train!)

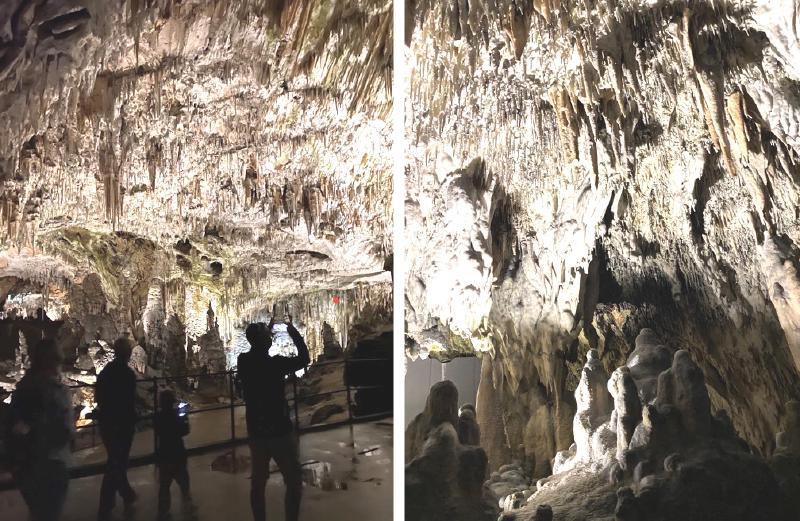

Cave diver and photographer Martyn Farr has produced a tempting array of descriptions and photographs of 100 cave and mine sites. Linda Wilson has done some armchair caving to bring you this review.

Hidden Realms aims to shine a light into some of the most alluring caves and mines in Great Britain and Ireland. One hundred sites have been chosen, in keeping with the recent vogue for examining the world and its history through carefully chosen places or objects. As a format, it’s proven popular and provides a convenient hook to hang a muddy oversuit on.

Martyn’s stated aim was to capture images of the underground world to captivate and inspire others and his usual high-quality photos ensure he succeeds admirably in that aspiration. A short introduction sets the scene for his work, conducted over two and a half years to ensure he had as many modern images as possible. The sites were chosen for various reasons, including sporting challenge and historical or archaeological significance and all the photographs were taken by Martyn, who acknowledges the help of numerous people, including his long-suffering models, who contributed to this project.

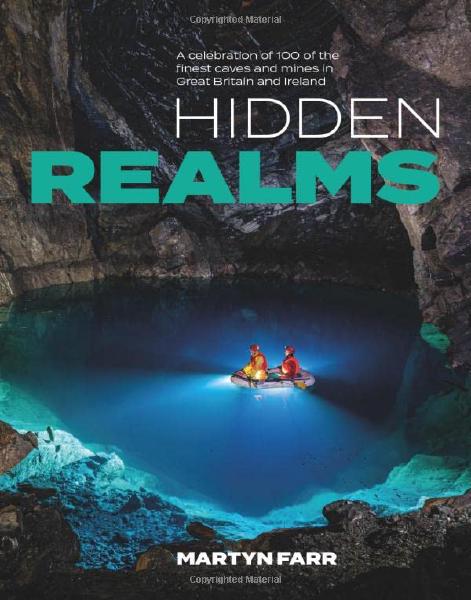

The book is divided into seven sections, each covering a caving region of the British Isles, with Wales divided into two, separating South Wales from Mid and North Wales, then Mendip and Southern England grouped together, followed by Peak District and Central England, then Yorkshire and Northern England, with Scotland and Ireland having sections of their own. Each entry covers two pages, with one main photo and some smaller ones, interspersed with enough text to provide context for the photos and to whet the appetite for a visit. My dominant reaction throughout was: “Oooh, I want to go there!” In some cases, I then read the accompanying entry and decided maybe that one wasn’t for me, but there were also plenty of times where I wondered why I hadn’t been there already.

For my local area of the Mendips and Southern England I thought the selection of 17 caves and mines/quarries provided an excellent representation of the region, ranging from well-known and popular classics such as Swildon’s, G.B. and St Cuthbert's to unusual caves like the hydro-thermal Pen Park Hole (next to a large Bristol housing estate) and Emmer Green Chalk Mine (in a Reading garden) with its profusion of historic graffiti, some dating back to the 1700s. Martyn has done a good job throughout the book of finding a balance between well-known sites and some hidden gems, Everyone is likely to find at least one surprise within its covers and I very much enjoyed the guided tour around regions that I’m less well acquainted with, whilst muttering “been there” when browsing other pages. The descriptions of the caves I know well I found to be concise and accurate. and throughout the book, the images are all well chosen for a balance between large, impressive passages, superb formations and unusual features.

Mendip's Withyhill Cave is displayed in all its glory, with the models simply incidental shadow for scale, whereas in Swildon's Hole, the focus is on a caver climbing the ladder at the Twenty Foot Pot, with a lovely interplay of movement, light and water amidst the formations. Accompanying this are smaller shots of a caver poised at the top of the Cascade Climb beneath the Forty Foot Pot, and one captured emerging from Sump 1 with water streaming out of her helmet.

Each section is prefaced by a very brief introduction, a whole page photo and a handy map, with major towns noted for context and each cave numbered against a list, although the numbering doesn’t appear elsewhere in the book, nor are page numbers given here for the later entries. The maps provided a useful overview of cave locations. All photos are clearly captioned at the bottom of each page. Naturally, Yorkshire caves feature prominently, with a good balance between pictures of cavers on impressively deep pitches and numerous shots of some very beautiful formations. The highlight here for me was a photo featuring the calcite boss in the main chamber of Sleets Gill Cave, with a superb relationship between light and shadow in the shot.

Hidden Realms is aimed at a general audience and does not set out to provide guidebook descriptions or access information. Anyone interested in visiting the sites will need to do their own homework, and although certain inferences can be drawn, it’s not easy to work out which sites are not, as Martyn states in the introduction, currently officially accessible and to which he was given special access. I do have some reservations about the inclusion of Mossdale Caverns as the tragedy on 24 June 1967 when six cavers were killed by flood water still casts a long shadow and I felt uncomfortable seeing what amount to tourist photos as the cave still remains a grave for some, although the images do help to explain its fatal attraction. My other very minor niggle relates to the number of photos with the model full face to the camera. For me, this often detracts from the surrounding scene, placing the caver at the forefront, rather than the cave, but I think this is very much in the eye of the beholder and is no reflection at all on the various models who all manage to hold a natural pose despite almost certainly having spent a lot of time hanging around, often cold and wet, during multiple attempts to capture the perfect shot.

As I expected, the photographs are superb throughout the book and are complimented by high production values from Vertebrate Publishing. In some ways, for me the mine entries were amongst the finest and most interesting, and so the North Wales section was a particular treat, showcasing an area I would very much like to get to know.

Hidden Realms is a fine testament to both the sporting and aesthetic aspects of caving and mine visits and is the perfect book to thrust under the noses of often incredulous and horrified friends and relatives, to show them, in the words of the song, ‘the reasons we go caving, and why we’re always there.’

1 June 2023

Paperback: 224 pages

Price: £25 A discount code of REALMS25 can be used.

ISBN-10: 1839810815

ISBN-13: 978-1839810817

With thanks to Vertebrate Publishing for donating a copy of Hidden Realms to the UBSS library.

We are Worm! Image produced by Bing Images.

- Awesome :D Also shout out to Guy for cycling to the hut with 1 broken pedal. [Merryn Matthews]

- A great newsletter as usual. I was particularly impressed by (and very envious of) the team effort in cleaning the Hut and its environs. I wish the GSG could muster a similar sized group to give our Elphin Hut the TLC it so desperately needs. If the UBSS team are suffering from withdrawal symptoms, we can offer another huge cleaning project for them to get their teeth into. [Julian Walford]

- Yes, of course I should be working! But the newsletter is so much more interesting. Great range of articles and some outstanding pix. I am still eeeeeeeking over the leeches story. And dearest madam editor, wasn’t there a story about you investigating AB (Dr)’s butt cheeks?! If you need sitty-downy stuff done at the museum, count me and the blessed FT Bear in. [Sharon Wheeler]

- So excellent to read of a new cave under a castle. [Chris Howes]

- Sorry I couldn't be there for the hut cleaning! Great newsletter as always! [Zac Woodford]

- I liked the comment from Steve Hobbs to the last newsletter the best bit in this newsletter (of course!). [Hans Friederich]

- Shamefully late but I needed to let you know how much I enjoyed reading about the adventures of Merryn, Miran, Mirian, Mirran, and Mirriam. [Mia Jacobs] {Editors' note: there's no such thing as shamefully late! And you're nowhere near taking David Hardwick's record of around 18 months late!]

Worm wishes, Wilfred!

THE END